About Brecht

Brecht out of fashion

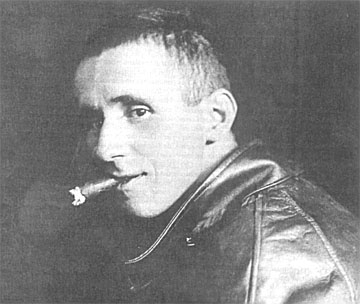

I am very interested in fashion. And since now even the hippie look of the late sixties has become fashionable again as grunge, and has naturally also disappeared the way fashion always does, I ask myself whether misery, poverty, and exploitation as literary subjects can come into and go out of fashion just as well. Brecht's leather coat, for example, this icon in the photographs, a piece of clothing deliberately sewn together crookedly (so that the collar would nicely stick out!), proves to me that appearance--that which is "put on" the literary subject matter--was very important to Brecht. But if the tireless naming of victims and their exploiters remains something strangely external to his Didactic Plays, something like a sewn-on collar (even though the naming of perpetrators and victims is really the main point), one could say that the work of Brecht, just like fashion and its zombies, very visibly bears the date stamp of his time. It is, however, exactly in the disappearance of the opposites, which are exposed as mere externals (misery and luxury, poverty and wealth), that the differences, strangely, come ever more irrefutably to the fore; and that is precisely what Brecht wanted! The basic tension, namely the gap between the real and what is said, is incessantly thematized by Brecht. Language fights against its subject matter, which is put on it like clothing (not the other way around!), a subject matter which is a piece of fashion; but how is one to describe fashion now? One can't. Thus the opposites master/servant etc., not unlike clothing, elude any description--even mock the very attempt at it. The real truth about these appearances we have to regain, time and again, from the codes of the externals by which the members of class societies are catalogued like pieces of clothing. That is to say, we have to look for the opposites behind the subject matters. Since we will not succeed, as little as Brecht could ever have succeeded in producing such a description (because the description would have used up everything that there might have been as its own raw material), there remains, even in Brecht's Didactic Plays, which seemingly are entirely congruent with their function, an ineffable, indescribable residue about which nothing can be said. And it is only about this residue that one can now talk.

Photo: Berliner Verlag

Measured extravagance

To dissipate utterly--that's something a poet likes to do. Only if he does that will be really become what he writes, will he disappear in it. Brecht wanted to give everything; but for that he had to take a lot, maybe more than others. And with him taking and giving are in a well thought-out ratio. In his case the giving takes place in a much more controlled fashion than with other authors, as far as I can see. Brecht took everything, especially much from women (which at the moment is everywhere a topic of discussion again)--women who have loved him, and who have worked on his behalf with the energy of their affection. Brecht then put everything in a blender--or maybe an hour-glass, which just had to be turned over every time it was empty. Brecht: a language agglomerate--sand that runs through sand, everything being indistinguishable from everything else. Often it is nourishment that flows, as Juergen Manthey, among others, has shown in his investigation of the noticeably developed orality of Brecht. Even a poet who knows times of hunger would not necessarily understand the emptiness in himself as one of the stomach, an organ which he may not always be able to distinguish from his consciousness. Consciousness imagines its subject matter, and compares it with what it means for Him Who Knows, i.e., contemplates the difference between truth and knowledge. That which Brecht knew about things he forced upon them in his work, suspecting that he may not have known things quite as well after all, and feeling that he had better tell it to these things once more, and repeat it, so that they wouldn't forget it. In this bifurcation, this permanent gap (the one that women have, too!) between his knowledge and his subject matter, he poured all that which is always at hand (and obvious for him who, in my opinion, always yelled for his mother, always opened his beak to collect tirelessly everything that was thrown into it) and imaginable: the grub. And only afterwards the moral--which, however, is always insep arably attached to the grub. But it is exactly in the intemperance of someone who constantly demands all sorts of nourishment that The Rule--postulated by himself, or provided for him--must be heeded: compulsory teaching. Emanating from the compulsion to dissipate. Roland Barthes, after all, has shown that the compulsive dissipation of the libertine de Sade was by no means without limits. The food, described in minute detail, is necessary to refill the sperm containers of the gentlemen (the description of the food for the prospective victims, by the way, is equally minute!)--just to get them ready to be emptied again. But order is reintroduced into the intricate description of all these nourishments and their preparation. Disorder is apportioned with great care, so that order can return as quickly as possible--the Didactic Play, the poem with a moral at the end (a poem written for the purpose of the moral!). But this precise determination is made by de Sade with regard to fornication, by Brecht with regard to artistic self-dissipation. The poet values this dissipation most highly (in part because he has an inkling that he has no choice in the matter anyway)--in spite of the discipline which time and again he brings about between his legs as well as at his writing desk, almost like a commodity (so that his women will stick with him). For there is always something left that is not under the control of the poet (who has sometimes thought as much), something that cannot ever be forced.

All or nothing

I've always had my difficulties with the work of Brecht, because of his--how shall I put it?--self-confident reductionism that keeps planing off, sharpening, and pointing its subject matter like a lollipop, until finally the specter of a sense comes out of the mouth of the actors, or the readers of his poetry--only to disappear irrevocably in the end. This is a work that grew out of danger, German Nazism. Yes, it did--and that's great about Brecht. The way he developed his subject matter: that's not some danger of existence as such, something that imperils human beings by way of fate, the emergence of humanity and its creations (art!) as some sort of necessary danger in the way Heidegger thought of it, for example. Brecht talks about the danger that comes from a system of theft and murder; he names and analyzes that system in all its ramifications, and in addition he takes a pointer and points out: this is the head of the danger, and this is its tail; and you always have to grab the snake by the head!

When one looks at the sketchy and playful improvement proposals concerning a few poems by Ingeborg Bachmann, the (disagreeably provocative) pointing madness of Brecht, which seems to clip poetry into shape like some bushes, becomes quite obvious again--an obsession with pointing which highlights what?--some sort of smart aleck forwardness? By thinning out these Bachmann poems, by supposedly bringing out their sense in a better way, the poems are merely deprived of their mystery, something that cannot be pressed into a formula for the purpose of getting some sum total at the end of the calculation. If one takes a closer look at these so-called improvements, to be sure, one will find that it is not a know-it-all attitude on the part of Brecht that makes him wield his pen, but clearly a kind of necessity, a deep-seated drive to create; it is this which prompts this author to plane off the chips which he sees. What's at work here is also not the concern of a good craftsman who tries to improve a piece so that it will get its proper form and function--which paradoxically always implies a neutralization (which Brecht doesn't want; he always aims at extreme concretization). What he aims at is something existential: this drive to remove the unnecessary is to result in a unification, a fusion of function and naming which constitutes a third thing, something which will then receive its correct name and categorization, so that one will end up with the only understanding of it that is possible. No misunderstandings, please! And if misunderstandings should come up anyway, well, they'll be taken care of right away! To achieve all this, Brecht pitches the most comprehensive opposites against each other: poor and rich, good and evil, stupid and wise, conscious and unconscious, etc. In order to avoid having to smooth out, to neutralize, Brecht makes the opposites do it themselves. And so they plane each other off--down to the handle, by which the lollipop is held. And that's always what you're left with: you've got a core, a statement, something that always looks the same. But there's nothing you can do with it anymore. It sums up everything without any remainder; and yet it summarizes nothing. But with what original passion did these petrified, drained-of-life opposites go at each other when the hand of the author let go of their hindlegs! Shrill yelping all around! It's possible that art which grows out of great danger cannot, as Brecht demonstrates so maniacally and obsessively, be allowed to veer out of control to reveal the unexpected. (In my mind this veering out of control comes out best in the work of Fleisser, who, one might say, was herself reduced to a skeleton by Brecht. For afterwards she overflowed her boundaries altogether to become something else, something extreme, something which couldn't be dammed up anymore by anyone.) Time and again Brecht's art must fuse the exemplary opposites into a final statement in which the greatest excess of our time, German fascism, can be seen to flow into every time and every place. From the exemplary to the extreme of ubiquity and generality!--for these are now plays for all times and all places, for every theatre and every weather. But perhaps that's not the problem of Brecht--the fact that the example becomes what everybody wants. Perhaps it's just the fact that today anything is possible which results in Brecht giving everything to everybody. Time, in a gigantic counter-move, has cancelled out all that planing off by rendering pointedness into ubiquitous generality. Only if our time would change (which nobody wants) could Brecht's drama be detached from the neutralization of its functions. I just notice that I am trying to describe Brecht's work as some kind of fashion, in the sense in which Roland Barthes, e.g., has developed a language of fashion; and indeed, Brecht's work strikes me to a peculiar extent as "fashionable". The more one wants to describe it as something that fits every time and occasion, the more visibly it reveals the date of its creation--which is also a way of refusing itself. And that, perhaps, is exactly the point: This work, in which everything (as I said so self-confidently earlier on) seems to fit together without remainder, ultimately resists (as I see now, while writing this) dating and incorporation after all; for a work of art cannot be everything, particularly not everything at the same time. Only a work of art can be everything, and everything at the same time at that; it can be, and it can have been. When the newest fashion in clothing dictates grunge, for example, i.e., when it turns that against which Brecht rose up like an enormous wave, poverty and exploitation, as well as its denunciation, into a mere appearance, then it paradoxizes both poverty and luxury. But in the disappearance of these opposites the differences come ever more irrefutably to the fore. Even though our time seems to make it possible for everything to co-exist, and even though this seems to turn Brecht into an "outdated", because too "fashionable", an author, he is nevertheless someone who doggedly keeps open the curtain in front of the differences, who even pulls it open if once in a while it threatens to close itself. Brecht's work doesn't deserve what it is getting. It isn't like some elegant Bauhaus structure, something that strikes us today and forever as "modern" because of its simplicity and its balanced, always fitting form, no matter whether it is located in the desert, in a big city, or high up in the mountains. This author, precisely because he tried so passionately to fit form and content together, to make them congruent, time and again tears open the gap, every gap; he even points to that which doesn't fit, which resists the solution to the riddle, to the intellectual puzzle. To me, in fact, it seems that that's the only thing he points to these days; and at this point all Meaning comes to a halt, and Art begins. Misery becomes luxury, poverty becomes chique, commitment becomes dulled--but nothing becomes simply neutral. Because for Brecht, the poet, the writer, it had to be that way, couldn't have been different; because what Brecht said is solid. And so he puts the sense into the dress of the form. And (because the form is constantly threatened by dissolution in the jogging course of time) both, exactly because they are threatened, become all the more noticeable. That's what happens when one tries to capture the ingraspable wealth of what exists by means of a simple system. Perhaps it doesn't mean anything anymore, but it had to be stated once. The rest is not work anymore, but--in its highest precision--a suddenly delirious speaking, speaking in tongues, about everything, and everything at once; and the precision becomes not a quod-libet, but everything that can be thought and said at all, because it leaves a tiny part that didn't fit into the whole, but which was nevertheless indispensable. Because this part took hold of the whole that was around it. Like the body of its dress, language.